Find the programme that meets your requirements and aspirations.

Apply nowSPJIMR blogs

- SPJIMR

- Blogs

- From isolation to belonging: Seeing life as an intelligent whole

From isolation to belonging: Seeing life as an intelligent whole

As I currently teach an elective on the ’Wisdom of the Bhagavad Gītā’ at SPJIMR SP Jain Institute of Management & Research for our MBA students, I often find that our classroom conversations move far beyond the text itself. They touch questions that many thoughtful, capable people quietly carry: Why does life feel so demanding even when we are doing many things ‘right’? Why does a sense of strain or isolation persist despite success, ethics, and self-awareness? The reflections shared in this article emerge from those conversations. Drawing from the Bhagavad Gītā as understood within the Advaita Vedānta tradition, I explore a simple but powerful idea: much of our psychological struggle may not stem from personal inadequacy but from how we understand life itself.

A great deal of human suffering does not arise from extraordinary misfortune or dramatic crisis. It arises quietly and persistently from a basic misunderstanding of the kind of universe we are living in. Traditional Advaita Vedānta points out that long before questions of liberation or self-knowledge arise, the human mind is already struggling, often unknowingly, with life itself. This struggle is not accidental. It is rooted in a failure to appreciate Īśvara as the grand, intelligent, lawful order that pervades and governs the whole of existence.

In this tradition, Īśvara is not presented primarily as a personal deity to be believed in, nor as a distant controller who intervenes selectively. Īśvara is understood as the total order of reality or, in other words, the universe functioning according to intelligible laws, relations, and regularities. Īśvara is the nimitta–upādāna kāraṇa, the intelligent and material cause of the universe, meaning that the universe is not separate from its order; it is the order manifest.

When this vision is absent, the individual unconsciously assumes a distorted standpoint: ‘I am a separate doer, standing apart from life, responsible for managing outcomes in a world that may or may not cooperate.’ This standpoint may seem normal, but it carries profound psychological consequences. To understand these consequences, we must first understand what is meant by ‘order’ in the Advaita sense.

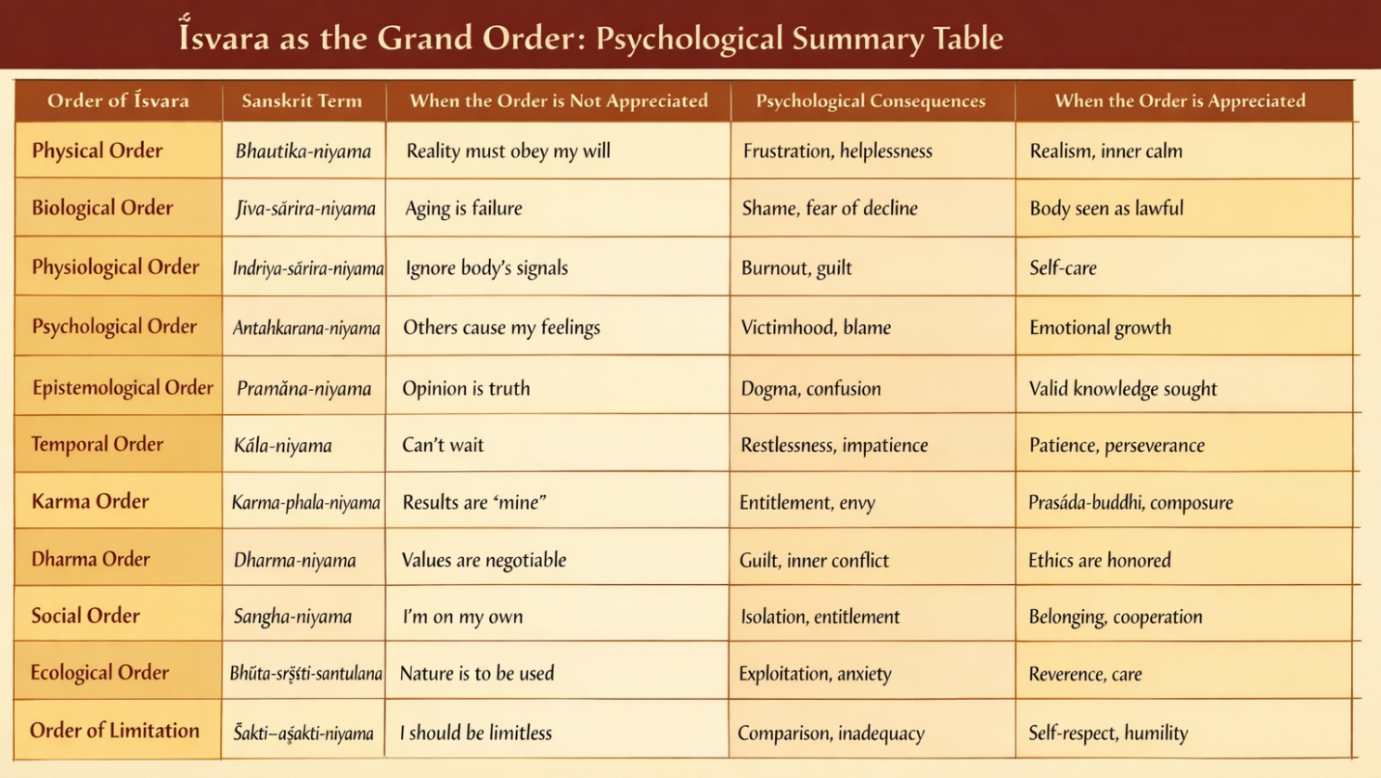

Īśvara as the many interrelated orders of life

The universe does not function as an undifferentiated mass. It expresses itself through multiple interrelated orders (niyama), each of which is a manifestation of the same Īśvara. These orders are not theoretical abstractions; they are encountered every moment of our lives.

There is first the physical order (bhautika-niyama), which governs matter, energy, space, time, and causality. Fire burns, gravity pulls, time moves forward, and physical processes do not suspend themselves to accommodate personal preference. This order is impersonal, predictable, and universal.

There is the biological order (jīva-śarīra-niyama), through which living bodies are born, grow, mature, decline, and die. Ageing, illness, and death are not errors in the system; they are integral expressions of this order. No human being, regardless of intelligence, success, or virtue, stands outside it.

Closely related is the physiological order (indriya-śarīra-niyama), which governs hunger, sleep, fatigue, sensory limits, hormonal balance, pain, and pleasure. These signals are not moral judgements; they are regulatory mechanisms through which life sustains itself.

There is the psychological or mental order (antaḥkaraṇa-niyama), which governs the functioning of thought, emotion, memory, desire, and response. Emotions do not arise directly from objects or situations; they arise from meanings attributed by the mind. Desire leads to action, action leads to results, results are interpreted, and interpretation leads to emotional response. This is lawful, not accidental.

There is the epistemological order (pramāṇa-niyama), which governs knowledge itself. Knowledge arises only through valid means (pramāṇa). Perception, inference, and verbal testimony function according to definite laws. Ignorance is not removed by effort, emotion, or experience alone, but by knowledge operating through an appropriate means.

There is also the linguistic order (śabda-niyama), which makes communication, teaching, and learning possible. Words have shared meanings established by convention. Even the śāstra functions because language itself is orderly and intelligible.

There is the temporal order (kāla-niyama), which governs sequence, maturation, and irreversibility. Some results are immediate; others require time. Growth, healing, learning, and the fructification of karma cannot be rushed.

There is the karma order (karma-phala-niyama), the law that connects intentional action (karma) with its results (phala). Every action produces a result appropriate to it, though not necessarily immediately or in a form one expects. This order does not reward or punish; it simply functions.

There is the dharma order (dharma-niyama), the moral and ethical structure that sustains harmony in human life. Values are not arbitrary social inventions; they are recognitions of what supports trust, safety, and inner coherence in relationships.

There is the social and relational order (saṅgha-niyama), which reflects human interdependence. No one is self-made. Each individual is born into a network of family, culture, language, institutions, and relationships that precede personal choice.

There is the ecological order (bhūta-sṛṣṭi-santulana), the balance among elements and life systems. Human life is nested within a larger web of life, not positioned above it.

Finally, there is the order of limitation (śakti–aśakti-niyama). Every individual has finite capacities. No one knows everything. No one can do everything. Omniscience and omnipotence belong only to Īśvara.

All these orders together constitute the one, intelligent whole that traditional Advaita Vedānta calls Īśvara.

Psychological consequences of not appreciating this order

When these orders are not recognised, the mind does not remain neutral. It adopts an erroneous orientation toward life, seeing itself as a separate agent confronting an unpredictable or hostile world. From this orientation arise multiple layers of psychological disturbance.

At the most basic level, there is conflict with reality. Physical laws, biological limits, and temporal processes are experienced as obstacles rather than facts. The individual becomes impatient with time, resentful of limitation, and frustrated by circumstances that do not bend to expectation.

When the biological and physiological orders are not appreciated, what is simply given is interpreted as personal failure. Fatigue becomes weakness, illness becomes inadequacy, and ageing becomes humiliation. This leads to guilt, shame, and a subtle rejection of one’s own body.

When the psychological order is misunderstood, emotions are externalised. People are blamed for anger, situations for anxiety, and circumstances for unhappiness. Emotional patterns repeat without insight, producing a sense of helplessness in one’s own inner life.

When the epistemological and linguistic orders are ignored, confusion deepens. Opinions are mistaken for knowledge. Experiences are mistaken for understanding. Doubt is not resolved but oscillates endlessly. In spiritual contexts, this produces either blind belief or chronic scepticism, both of which exhaust the mind.

When the karma order is not appreciated, results are taken personally. Pleasant outcomes inflate the ego; unpleasant outcomes wound the self. There is a sense of entitlement: ‘I did my part; therefore, I deserve a particular result,’ followed inevitably by disappointment and resentment.

When the dharma and social orders are disregarded, ethical compromises produce inner fragmentation. Even when such compromises appear externally successful, they generate loss of self-trust, fear of exposure, and quiet unrest.

When the order of limitation is ignored, comparison becomes relentless. One oscillates between arrogance and inadequacy, measuring oneself against unrealistic standards and resenting both oneself and others.

Isolation, estrangement, and the sense of separation

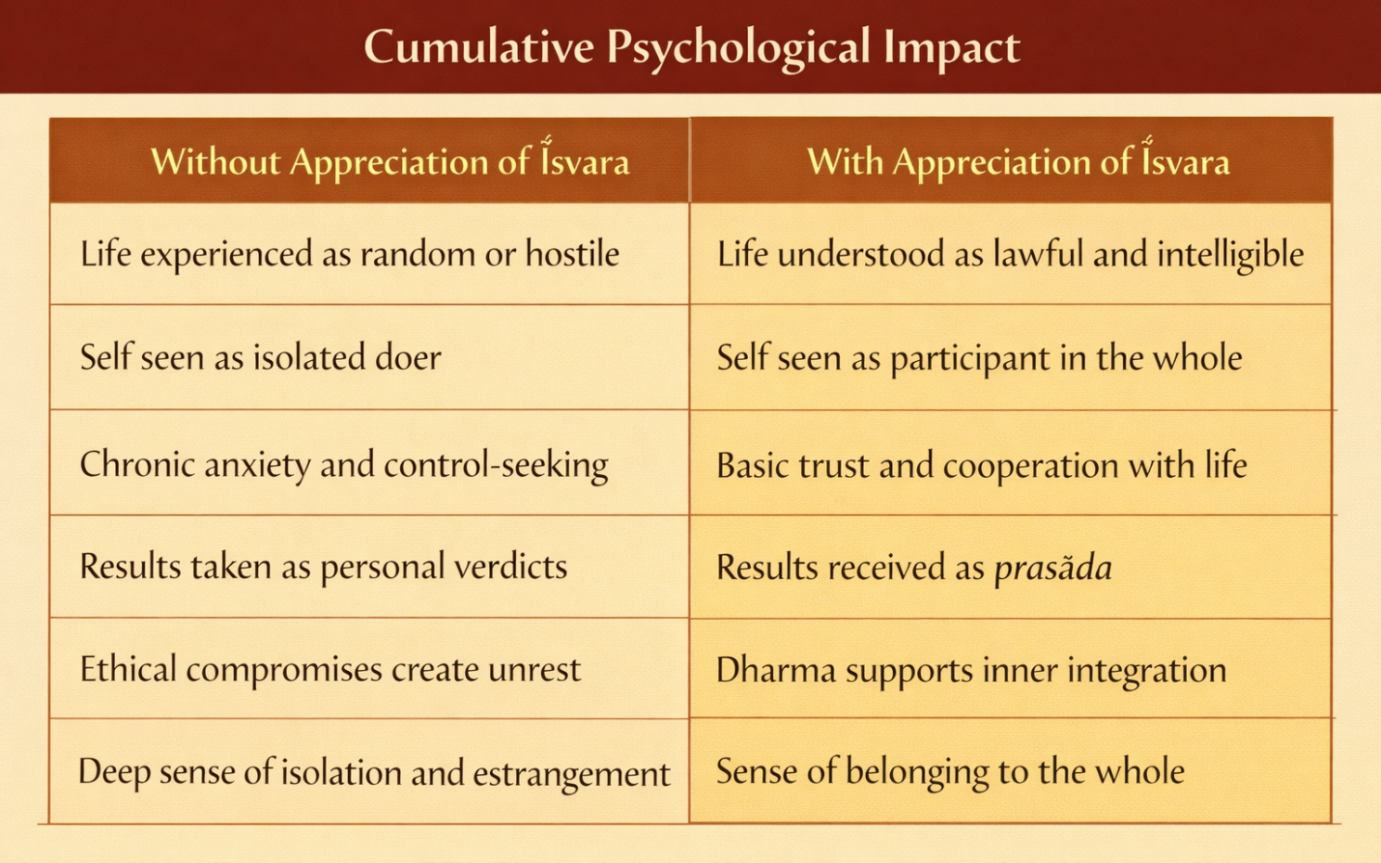

When all these misreadings accumulate, the psychological outcome is deeper than stress or anxiety. It is existential isolation.

The individual experiences themselves as fundamentally alone—separate from life, standing outside the universe rather than within it. The world feels indifferent, hostile, or absurd. Life appears as something to be managed, controlled, or survived, rather than understood and participated in.

This condition can be described as estrangement, a sense of not belonging to the whole. Even in relationships, even in success, there is a quiet loneliness. One is, in effect, cosmically homeless.

Traditional Advaita Vedānta recognises this as saṃsāra at the psychological level: a life lived under the weight of separation long before any explicit inquiry into the nature of the Self begins.

The psychological shift when Īśvara is appreciated

When a person begins to appreciate Īśvara as the grand order, the external facts of life do not change. The same laws operate. The same limitations exist. The same responsibilities remain. What changes is the orientation of the mind.

The individual understands, perhaps for the first time, ‘I am not an isolated doer in a random universe. I am a participant within an intelligent, lawful whole.’ Life is no longer something happening to the individual; it is something the individual is within.

Physical and biological limits are accepted without humiliation. Time is respected rather than resisted. Knowledge is sought through proper means rather than forced. Action is undertaken fully and responsibly, but results are received with prasāda-buddhi, as lawful outcomes arising from a vast network of factors.

This produces samatvam, inner steadiness and composure, not indifference, but maturity. Success evokes gratitude rather than arrogance. Failure evokes learning rather than collapse.

Most importantly, the deep sense of isolation begins to dissolve. There is a quiet sense of belonging, not through emotional fusion or mystical experience, but through clear understanding. One belongs to the whole by fact, not by effort.

A closing reflection

Traditional Advaita Vedānta, as articulated by my teacher Swami Dayananda Saraswati, insists on this realism as a foundation. Without an appreciation of Īśvara as order, the mind lives in subtle rebellion against reality and pays for it psychologically through anxiety, resentment, guilt, and isolation.

With this appreciation, the mind becomes grounded, ethical, resilient, and available for deeper inquiry. The wound of separation begins to heal, not through belief, but through understanding.

Before asking, ‘Who am I?’ one must first understand, ‘What kind of universe am I living in?’ When that universe is recognised as a manifestation of Īśvara as order, the individual no longer stands apart from life but finally finds their place within the whole.

And yet, an important question remains. Which I will explore in the next article I will publish soon.

Tables as a summary

Psychological summary table

Cumulative psychological impact

The reflections in this article draw primarily from the teaching tradition of Advaita Vedānta, which I studied from Swami Dayananda Saraswati. If you are interested in exploring these ideas further, you can refer to the following works and links.

1. Bhagavad Gita – home study course (set of 9 volumes) – Swami Dayananda Saraswati https://www.amazon.in/Bhagavad-Gita-Course-Volumes-English/dp/9380049390

2. Living the vision of oneness and finding meaning in life with the Bhagavad Gita – Neema Majmudar and Surya Tahora https://discovervedanta.com/english-publication/

Rate this blog

Ratings

Click on a star to rate it!

Rated 0 based on 0 user reviews

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

About the faculty

Surya Tahora

Surya Tahora is a professor in the area of general management at SPJIMR. He teaches Spirituality and Leadership to around six hundred MBA and Executive MBA students annually and conducts workshops for various organisations in India, Europe, and Asia.

More from Surya Tahora

Recent faculty blogs

-

When the informal economy competes, innovation gets rewritten

Read more -

When fairness fails, people withdraw: The hidden cost of unfair workplaces

Read more -

Why ‘more salespeople’ is not the answer in emerging markets

Read more -

Can behavioural finance help build a more inclusive investment ecosystem in emerging economies?

Read more -

“What’s in a name?” A discourse on brand naming

Read more

Most read faculty blogs

-

Organisational responses to hybrid work—Rethinking culture and civility in India

Read more -

When Amazon arrived late to India’s quick commerce party

Read more -

Reimagining travel through AI: Making every journey smarter and more personal

Read more - Read more

-

Inside stories of Crime Patrol episodes

Read more